Consumers stockpiling in supermarkets around the world is already a concern for local supply. But what happens if the key exporting regions also decide to stockpile? It looks like we’re about to find out.

The latest system to feel intense pressure from the coronavirus pandemic is global food supply, confirmed by the UN releasing a statement of concern last week. They said; “We must ensure that our response to Covid-19 does not unintentionally create unwarranted shortages of essential items and exacerbate hunger and malnutrition”. This concern has its roots in the changing policy of many nations. Several countries have now put limits on commodities such as rice, grains and oils, leading analysts to question if this behaviour will become more widespread and create knock-on effects for all.

Production across commodities should be relatively stable this year, provided we don’t experience adverse weather or large staff losses due to illness. For example The IGC (International Grains Council) estimates the world will produce 2.2 billion tonnes of grains in 2020, which is up 2% from last year. The wheat production estimate has been adjusted up by 5m tonnes to 768m tonnes for the year. However, just because commodities are being produced does not mean they will reach the people who need them, due to a number of factors outlined below.

How Will Coronavirus Impact Global Food Stocks?

The impact on global food supply in the coming weeks and months is at present unclear, partly because it varies depending on how large a share of the market a particular region holds, and how their policies might change. Russia for example is one of the world’s largest exporters of wheat, calling into question where supply will be found as an alternative as they reduce their output.

In the short term, the reasoning behind such activity is clear. Countries are driven to limit exports in order to protect domestic supplies and stabilise price. However, if this behaviour continues and spreads further, we may be in a more challenging situation with rising demand and prices. The irony of national stockpiling is its negative effect on the domestic producers (farmers, mills, etc) who cannot properly leverage the new demand nor benefit from any global price spikes. This in turn leads to internal economic challenges in these countries.

The Impact on Importers

Collectively, the world’s top twenty producers of grains, cereals and staples account for over 80% of the supply into Asia, Africa and the Middle East. While the Asian and Middle Eastern economies have displayed some level of stability in the face of such crises, the biggest threat is faced on the African continent, where some of the poorer nations are majorly net food importers.

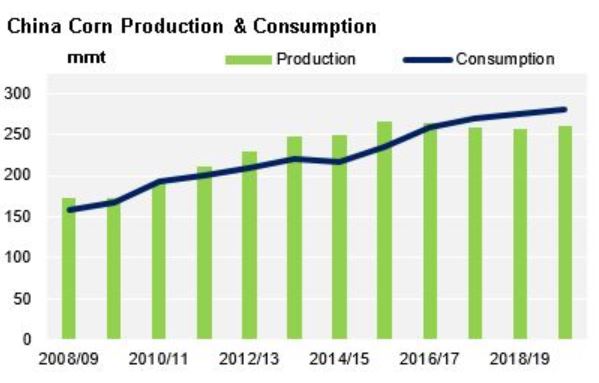

China and India, as the most populous countries, have the greatest need for food commodity stocks. Current numbers suggest that these two countries alone will have 170m of the total 287m tonnes of global end-of-year wheat stocks. Currently Chinese corn consumption is higher than production, outlining their predicament.

North African and the Middle Eastern countries urgently need food security as their climates make self-sufficient production a challenge, but questions about their ability to finance the necessary imports remain unanswered. As March turned to April, Algeria bought 240k tonnes of wheat and 250k tonnes in tenders. Turkey has been on a wheat buying spree over recent weeks and Saudi Arabia has bought over 1m tonnes of grains.

Egypt, the world’s largest importer of wheat, has stated a clear intention this week to increase wheat stockpiles to avoid any potential lockdown and logistical problems. Their concerns were made clear last week, when they put out a tender which was cancelled within minutes, stating that any seller would have to guarantee delivery, regardless of any logistical issues. This would include the seller accepting any extra cost burdens due to having to source an alternative origin wheat to fulfil sales, at the seller’s cost. Clearly, they wish to avoid any potential of ‘Force Majeure’ issues and have also introduced a ban on exporting legumes for the next 3 months.

The Impact on Price

As consumers stockpile supplies for lockdown at home, they also create more demand and strain on producers and supply chains at home and abroad. What would normally be bought to last a week is now multiplying into stocks for a month as communities anticipate ongoing lockdowns. This action drives up prices, as has been exemplified in the wheat market:

Sudden price spikes in countries with a limited capacity to respond to shortages typically result in a rapid exhaustion of buffer stock, followed by a decrease in affordability for the consumer leading to poverty and starvation. In a global pandemic, the last thing we want is to weaken the immunity of the population through hunger and increase their susceptibility to the virus.

Which Countries are Withholding Supplies?

As previously mentioned, a number of countries have introduced policies to limit the amount of exports they will make this year. The main players on our radar are:

Russia

- The world’s largest wheat exporter, and second largest exporter of grains (buckwheat, rye, sun seeds etc), has implemented export restrictions to protect domestic supplies.

- This could have been brought about by the fact that Russian exports of wheat jumped 35% in the first three weeks of March from a year earlier, leading to fears of ongoing domestic sercuity.

- They have recently introduced an export ban, stating that grain exports cannot exceed 7m tonnes in Q2’20.

- This is unlikely to have a large impact on supply as this volume is roughly what Russia was expected to ship in the quarter.

- Russia will also release 1.5m tonnes of its1.8m tonne grains stockpile into the domestic market from April 13th to ensure supply to millers and bakers.

- Russia has a history of influencing the global market by restricting exports through taxes, bans or informal limits. We will watch closely to see how their plans develop.

Ukraine

- As a major grain and vegetable oil exporter, Ukraine is monitoring its wheat exports on a daily basis, amid growing concerns from local millers of bread and flour surrounding domestic prices.

- It has limited wheat exports to 20.2m tonnes this year.

- Wheat exports in April are running at around 14k tonnes per day, versus 44k tonnes a day in March.

Kazakhstan

- Along with Russia and Ukraine, Kazakhstan is responsible for approximately 60m tonnes of the 183m tonnes of global wheat exports this year.

- Here, there was a collective ban on the export of wheat flour (not kernels) before the introduction of quotas. Also included in the ban were buckwheat, sugar, sunflower oil and staple vegetables (e.g. potatoes and carrots).

- This ban is a stockpile measure and will be in place until at least 15th April.

- The move could directly affect Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, whose staple grain supply comes from Kazakhstan, as well as the global flour market.

- However, Kazakhstan is not a major exporter of sugar so this ban will have no effect on the sugar market.

Vietnam

- Vietnam, the third largest exporter of rice, temporarily suspended all rice export contracts on the 28th of March to check domestic stock levels.

- The Trade Ministry yesterday asked the government to resume rice exports, but to limit them to 800k tonnes in April and May.

- This is 40% lower than last year’s volume in this time period.

Serbia

- Serbia have banned all exports of sunflower oil and staple vegetables.

Cambodia

- As of the 5th April, Cambodia will be limiting rice exports until further notice.

- This comes after prime minister Hun Sen expressed concerns over food security.

Thailand

- After seeing their export price rise amidst neighbouring countries introducing bans, Thailand have placed similar export limitations on rice and other major staples.

India

- Due to the current lockdown, India are no longer accepting new rice contracts.

- This is mainly due to a lack of workers and disrupted logistics.

The Impact of Port Restrictions

Port restrictions have increased in recent weeks, with more countries facing difficulty in moving goods. As logistics solutions become impaired, the supply chain slows down and bottlenecks which can create further strain on current low supplies. This is having a major impact on food supply globally as slowed services are leading more countries to stockpile for safety.

Sanitation and safety are becoming increasingly key factors and are leading to countries like Brazil quarantining ships for two weeks before allowing them to enter or leave ports. Algeria, Ireland, Mozambique and others are enforcing stricter safety checks on the health of ship staff. Where ports are open the service is expected to be greatly delayed. The US is one of the countries with the most ‘business as usual’ approach. You can read a full report on the latest port updates on Czapp.

Weather: Yet Another Uncontrollable Factor

In a normal year, weather has a high impact on crop yields but with more strain on supply chains, finance and exports, weather will play a more determining role than ever before. The coming months will make or break the 2020 harvests across a range of commodities. Food security will be dependent on helpful weather, which unfortunately like the virus is a factor we cannot control.

We are just starting to see the first meaningful crop reports for 2020. Some are stark, with France reporting estimates of a 7.5% decrease in soft wheat plantings. The UK and Hard Red Wheat in the US looking uncertain we will be watching grain crops closely. Sugar, as we have reported, has been strong in the world’s largest producers India and Brazil.

Looking Ahead

The coronavirus dominates market movements everywhere. Lockdowns and logistical problems have the ability to disrupt the normal trade flows and, as a sobering consequence, the ability for the importers to feed their nations. If countries increase stocks, they should, at the very least, buy themselves time. Exporters’ own concerns, as we already see in the Black Sea area, may lead to additional trade adjustments as they sure up their own domestic markets.

At Czarnikow, we commit to being vigilant in identifying and mitigating emerging risks and work to ensure food is accessible for all. This requires flexibility, transparency and innovation, and we will be doing our utmost to support stable, ongoing food supply for all.

We also look to our policy-makers and leaders during this time of intense difficulty. It is important for governments around the world to think of others and not just themselves: not only is this fair but it benefits everyone in the long-run and reduces the appetite for conflict, environmentally exacerbated suffering and bail-outs.

Author: Carys Wright

Images: Sandy Zebua, Meric Tuna, Davi Mendes and Andy Li