In our first two blogs in this series, we have looked at The Paris Agreement and COP and how these have set the agenda for all things relating to carbon emissions. In this blog we’ll dive a little deeper into the different types of carbon emissions, their implications and challenges, and companies pledges to reduce their carbon footprints.

What is a ‘scope’ when it comes to emissions?

If you’ve read around the carbon topic, it’s likely that you’ll have heard of the term ‘scope 3 emissions.’ But what does this mean? Before we can look at scope 3 in more detail, we need to explain the framework that supports it.

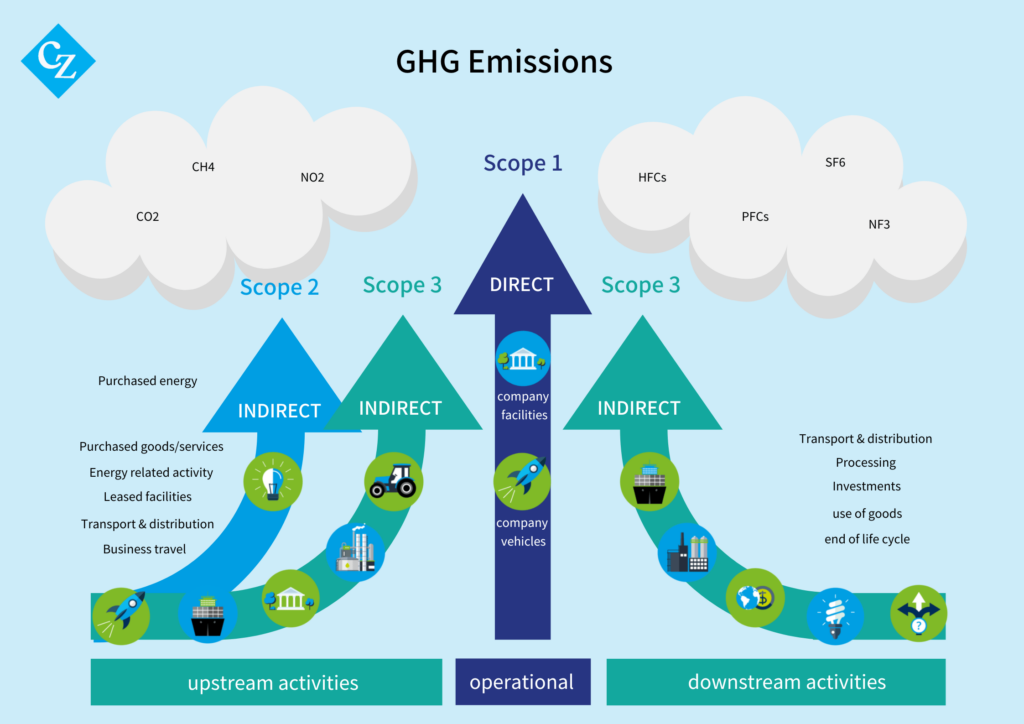

Greenhouse gas emissions (of which carbon emissions form the majority) are categorised into three groups, called ‘scopes.’ This terminology was originated by the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol, which provides the most widely used GHG accounting standards. The scopes are split into three so that it is easier to determine where each emissions scope is coming from, and therefore where and how to identify specific reduction plans.

The scopes are:

- Scope 1 – direct emissions resulting from owned or controlled sources

- Scope 2 – indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy

- Scope 3 – all indirect emissions from the value chain of the reporting company, including both upstream and downstream activity.

Scope 3 emissions

Now we understand a bit more about scopes in general, let’s take a closer look at scope 3. As explained above, scope 3 covers all indirect emissions. This means the whole value chain of the company is taken into account from the emissions of its suppliers and the consumers of its product or service. Value chains, or the whole lifecycle of a company’s activity, are important to consider when measuring carbon footprints because they often represent more than 90% of a company’s total emissions. This is therefore the area where companies can make the largest impact in terms of reductions.

While the large numbers associated with scope 3 emissions can be daunting, calculating scope 3 can bring a range of opportunities, including:

- Identifying key risks and opportunities for the business’ future

- Identify key ‘hotspots’ for carbon emissions within a business’ value chain

- Identifying reduction opportunities that can make permanent change to a company’s strategy or business model (e.g insetting)

- Engaging key stakeholders in GHG management and reductions

- Enhance transparency in the climate change sector at large by reporting on emissions over time

Reporting scope 3 emissions

Because of the scale of scope 3 emissions, several initiatives have called for disclosures of scope 3 emissions. The task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) made scope 3 a key point of their updated recommendations, requiring public companies to report their scope 3 emissions annually. Reporting scope 3 emissions builds transparency, which is an essential step towards a full understanding of how we can act to reduce carbon emissions to fall in line with the Paris Agreement.

Why are scope 3 emissions so hard to calculate?

The main challenge in calculating scope 3 emissions is data, or rather lack of it. Accurate scope 3 calculations require data from all areas of a business’ supply chain – including the emissions of its clients, suppliers and service providers. Each one of these may calculate in a slightly different way, or have different blind spots where data is not collected, is collected manually or is not centralised. Moreover, there is no consistent way of accounting for scope 2 and 3 GHG in national and international policy.1 The growing importance of scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions from industry – IOPscience This means that at the moment some of scope 3 calculations must involve assumptions or industry averages based on relatively large datasets such as location, size of company, technology and machinery used and so on. This is done by using the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, the main setter of agreed standards by which to measure emissions.

Another challenge is that double counting may occur when emissions are counted in several companies’ value chains, especially if those chains are linked. This causes uncertainty about which business is responsible for reducing said emissions, and how these reductions should be actioned. Boundary setting is also a challenge here, as depending on a business’ activity they may be present at various points in the lifecycle of products.

How science-based targets help reduce supply chain emissions

A science-based target is a goal pursued to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, thus contributing to the goal of keeping global warming at 1.5 °C this means a company that pursues science-based targets aims to align with The Paris Agreement. Science-based targets as a tool should not be conflated with the Science-based targets initiative (SBTi) or the Science-based Targets Network (SBTN), both of which are private organisations that provide corporations with strategies to reduce emissions. SBTi is a partnership between four leading climate action groups: Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), UN Global Compact, World Resources Institute (WRI) and The World Wildlife Fund (WWF). SBTi provides companies with criteria, or pathways, for cutting down their climate emissions.

SBTi’s target setting methods are built on:

- Assigning a carbon budget;

- Presenting a way of distributing the available carbon budget over time;

- A plan for allocating the carbon based on a given emissions scenario. SBTi factor the possibility of all companies in a sector reducing their emissions intensity to a common value, and all companies reducing their absolute emissions intensity at the same rate.

It’s important to note that SBTi prioritises the actual reduction of GHG emissions over the use of offsets.

Target setting approaches differ by sector. Organisations with little physical assets tend to turn to carbon offsetting to become carbon neutral or net-zero. At least 1000 companies have adopted science-based targets or committed to net-zero emissions or climate neutrality but whether SBT accurately assign emissions to these companies is unclear. This does not mean we should scrap SBT altogether, they are still a useful tool for the private sector. More transparency on voluntarily set SBT is necessary for governments to develop new policies need to be introduced in alignment with The Paris Agreement.2 Can Science-Based Targets Make the Private Sector Paris-Aligned? A Review of the Emerging Evidence | SpringerLink

Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture-food systems

A 2022 study on global food miles, published in Nature Food, found that upstream food supply chains account for nearly 20% total food-systems emissions, with 36% coming from freight for fruit and vegetables. Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions | Nature Food. Some consumers are turning to seasonal eating to reduce their carbon footprint, but to reduce excess volumes of GHG that come from farming the key crops that sustain much of our world’s population, wheat and rice for example, farming practices will need to adopt precision agriculture to maximise efficiency and yield. Obviously, the ways we transport these agricultural goods need to be more environmentally positive. Read our blog on the ways the shipping industry aims to cut its emissions here.

One investigation of ways to transform agri-food systems reported that virtualisations (computer simulations) of supply chains help uncover the optimal behaviour of the players in a chain, and account for setbacks that occur because of climate change. Obviously, this kind of technology cannot be rolled out globally because of economic limitations. But the principle stands: identifying and implementing optimal waste management and biological conditions is a necessary step toward a circular agri-food economy. These kinds of action must be supported by the food and beverage manufacturers that consume agricultural products.

Emissions targets in the food and beverage industry

Food and beverage manufacturers have some of the largest scope 3 emissions, as they have a very long upstream value chain. Therefore, these companies are under pressure to reduce emissions and publish action plans as to how they will reach these targets. A report by the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) in 2021 found however that of the largest 350 food and agriculture companies, together accounting for over half of the world’s food and agriculture revenue, only 26 were working to reduce their scope 1 and 2 emissions in line with the Paris Agreement. Only seven had set time-bound targets for their scope 3 emissions in line with the UN’s 1.5°C warming target. Pressure is on these companies, as by 2050 not only have ambitious targets been set for net zero, which you can find on their websites or annual reports, but it’s also estimated the world will need 50% more food. We will have to rapidly find solutions to feed the world in a low-carbon way.

How will food and beverage companies get there?

While these high-profile emissions reduction pledges are encouraging, some claims have come under scrutiny for their lack of clear focus, or their revised, delayed date targets. The Net Zero Tracker, created by a team of NGOs and researchers, has found that over one third of the world’s largest public companies have set net zero targets, but 65% of those do not yet meet minimum reporting standards. There is room for improvement they state that the overall transparency and integrity of net zero pledges studied is far from sufficient in ensuring a timely decarbonisation in line with The Paris Agreement. The Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor has similarly discouraging findings. Methodologies for reducing carbon emissions among two thirds of the large corporates it analysed, which together amount to around 5% of global GHG emissions, are overly reliant on offsetting through forests and other natural processes which can easily be reversed, for example by forest fires which the news tells us are increasingly prevalent.

Some large companies, like Walmart, have announced net zero pledges but have failed to take scope 3 emissions into account, rendering their pledges far less valuable than they appear at first glance. As large multinationals come under closer scrutiny, risks of greenwashing have been made apparent.

A collaborative approach to decarbonisation

The ambition of many of these corporate pledges makes it clear that a huge amount of collaboration will be needed for them to be achieved. As we have explained above, scope 3 emissions are particularly complex, and the larger the company, the more data that needs to be collected, the more supply chain participants that must be involved, and more rigorous use of standardised accounting is needed. Challenges in reducing scope 3 are widespread, for example Unilever have discussed how outside their laundry products, they have little influence on how washing machines are run in terms of energy supplier and machine model. They point to grid transformation as a faster solution than changing consumer habits in this area.

By developing VIVE Climate Action and grounding it in the sustainability credentials and experience of the VIVE Sustainable Supply Programme, CZis now at the forefront of decarbonisation in the sugar industry. Our supply chain management expertise puts us in a unique position to solve the challenges of large food and beverage corporations’ scope 3 emissions. We can influence supply chain actors like farmers, processors, and logistics companies to take steps towards reducing their emissions through a combination of data collection, commercial incentives and longstanding relationships. We will touch on this in more detail in our next blog.

Sources

https://www.carbontrust.com/resources/briefing-what-are-scope-3-emissions

https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards_supporting/FAQ.pdf

https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/climate/scope-three-challenge.html

https://www.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/publication/food-agriculture/

https://zerotracker.net/analysis/net-zero-stocktake-2022

https://time.com/6117635/companies-net-zero-greenwash/

Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor 2022 | NewClimate Institute